A new report shows three Kiwis – and rising – a week are dying from accidental drug overdoses.

A grieving mum is backing those working to prevent drug harm through more drug testing and increased access to opioid reversal medicine.

The woman’s 20-year-old daughter died in 2022, with post-mortem tests showing the Wellington student had nitazenes and alcohol in her system.

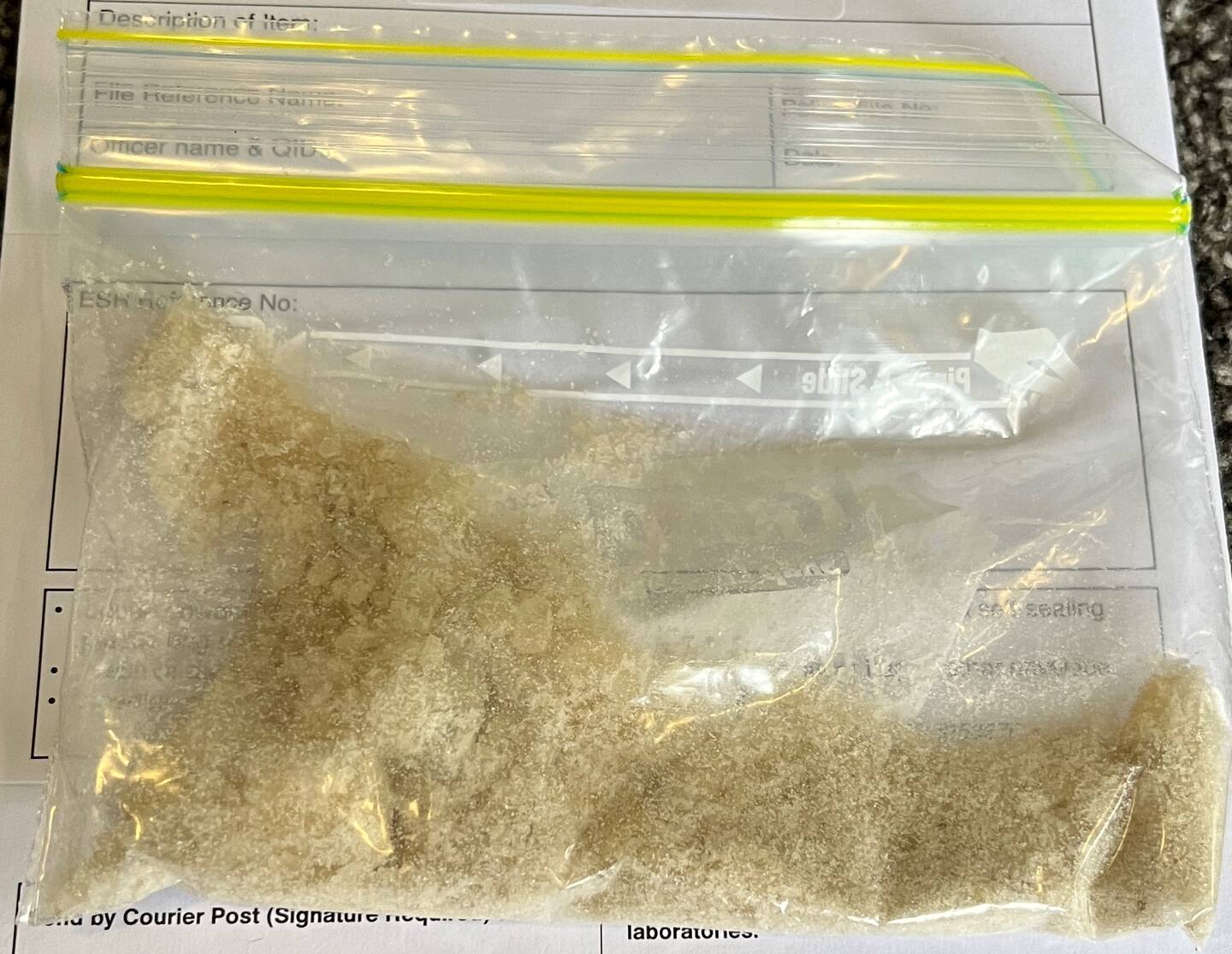

Nitazenes are a family of lab-made opioids so potent, drug safety advocates call them the “new fentanyl” – after the drug that causes tens of thousands of deaths in the United States every year – and say a dose as small as a grain of sand can kill.

They’d been seeing nitazenes sold as other drugs in New Zealand, drug information website The Level wrote on Instagram in May.

“The most recent finds were sold as benzodiazepines, but they’ve also been sold as weaker opioids (like fake Oxycodones), and as MDMA and ketamine in Australia.”

The woman, who asked not to be named, believed her daughter didn’t know she was taking the dangerous opioid.

“If my story can save one life, that’s what’s important to me … I want the stigma taken away, and I want easier access to testing of these drugs so our young people are aware of what they’re taking.”

The young woman, who worked part-time in hospitality and dreamed of travelling the world, was among 1179 people to die in New Zealand from accidental drug overdose between 2016 and 2023, according to the Drug overdoses in Aotearoa report released today by the NZ Drug Foundation Te Puna Whakaiti Pāmamae Kai Whakapiri.

Opioids were the biggest contributor, with 516 having taken at least one opioid before their deaths and – whether or not it was the cause of death – 35.4% of fatal overdoses involved alcohol.

The risk of overdose from opioids increases when a person takes another depressant drug at the same time.

Alcohol could also add to the risk of overdose death, especially when mixed with other depressant drugs such as opioids, benzodiazepines or synthetic cannabinoids.

Almost two-thirds of those who died were male, and Māori had a fatal overdose rate 2.4 times higher than non-Māori, according to the report released by the foundation on International Overdose Awareness Day.

People aged 45 to 54 had the highest overdose mortality rate of any age group.

The report’s findings were heartbreaking, foundation executive director Sarah Helm said.

“Each of these numbers represents a person whose whānau, friend group and community has been ripped apart.

“I think New Zealanders will be appalled to see the number of preventable overdoses in our country is continuing to increase.”

As a society “we simply should not tolerate it”, Helm said.

“We’ve rightly spent millions of dollars to turn around our road and drowning tolls. We need to do the same for drug overdoses.”

The predominance of opioids in fatal overdose statistics, along with the emerging threat of potent synthetic opioids like nitazenes, showed why increasing access to naloxone – an opioid overdose reversal medicine – was crucial.

“We need to get naloxone into the hands of the community – both to turn around this unacceptable number of overdoses, but also to prepare us for what’s coming with nitazenes making their way into our drug supply.”

An expert Pharmac committee had recommended the agency fund nasal spray naloxone for people at risk of opioid overdoses, after an application from the foundation.

The Drug overdoses in Aotearoa report also included, for the first time, data on non-fatal overdoses.

This showed hospitalisations for drug poisonings had steadily declined over the last five years.

It was concerning this hadn’t been matched by a fall in fatal overdoses, Helm said.

“It could be due to high potency opioids in the illicit market increasing the likelihood of death, and decreasing the likelihood that someone makes it to hospital. It could also show that people aren’t seeking help when they need to.”

A Good Samaritan law legally protecting people seeking help for themselves or others overdosing was a way to encourage people to get the help they need.

“There are also some concerning discrepancies between those who are dying from overdoses compared to those who are making it to hospital.

“For example, 45-54-year-olds have the highest rate of overdose deaths, but that same age group isn’t presenting at hospital more frequently than other groups. We need to understand what is going on there.”

Because there’s no national overdose surveillance system, the report’s authors used coronial data, hospital presentations for drug poisonings and Health NZ national mortality data to determine the harm from accidental fatal and non-fatal drug overdoses.

Overdose deaths rose from 133 in 2017 to 188 last year, up from 156 in 2022. The most recent deaths were likely to still be under investigation, so are provisional and may change in future, according to the report.

They were still waiting for a coronial hearing into her daughter’s death almost two years on, the mother said.

She knew her “happy” and thriving daughter liked to “have a drink and party, like you do at that age”.

But she’d previously spoken to her about making sure any drugs she took had been tested, and fentanyl test strips - which wouldn’t have detected the nitazenes - were found in her bedroom.

“I had a conversation with her … about being careful and making sure she had things tested, because you can’t stop young people doing these things.

“And she was like, ‘Yeah, absolutely onto it’.”

Police had checked her daughter’s phone and laptop and weren’t able to find out where she got the opioids, the woman said.

They told her family the drug was thought to have only been in Wellington a few days before the 20-year-old’s death.

“We believe she probably got it on the street, or maybe at the bar, someone just gave it to her.”

She backed calls for more access to naloxone, and encouraged anyone taking drugs to make a safety plan that included making sure they weren’t alone.

“If she’d had someone with her, they might’ve been able to raise the alarm.”

Her daughter was a “strong, smart woman with her life ahead of her” but that had been cut short by a “stupid mistake” that shouldn’t have happened.

“She had all these ideas and dreams and goals, and she just wanted to live.”

Cherie Howie is an Auckland-based reporter who joined the Herald in 2011. She has been a journalist for more than 20 years and specialises in general news and features.